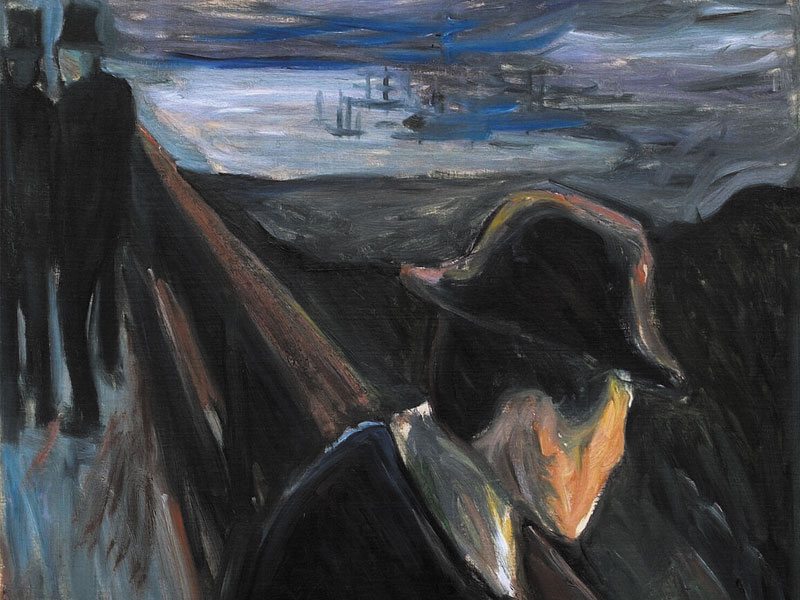

Edvard Munch, Sick Mood at Sunset. Despair, 1892. Thielska Galleriet, Stockholm. (Courtesy of SFMOMA)

(Published in SF Weekly on June 29, 2017: http://www.sfweekly.com/culture/art/scream-and-shout-edvard-munch-at-sfmoma/)

Surrounded at an early age by familial deaths from tuberculosis, an ominous fear that he would be “next,” and the worrisome nature of his religiously conservative father, Edvard Munch was on edge through much of his life. This sense of unease infused his work with a psychological and emotional dimension that reached an apotheosis with The Scream, the 1893 painting that has been embedded in popular culture for generations. Munch was not quite 30 years old when he did his first iteration of The Scream (or Skrik, in Norwegian). But he lived another 50 years, until 1944, and he continued to produce work — lots of work — that is as stellar as The Scream for its raw, painterly portrayal of inner and outer turmoil. Can the average art-goer name one of these later works?

In a word: No.

That may change with “Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed,” SFMOMA’s new exhibit that — thanks largely to the museum’s collaboration with Norway’s Munch Museum — looks at the artist’s entire career, leaning heavily on Munch’s post-Scream oeuvre. Taking its title from a self-portrait that Munch did between 1940 and 1943, the show is a revelation for the way it burrows into Munch’s methods of working a canvas and his way of seeing the world.

Throughout his life, Munch had tense relations with women, and his 1925 work Ashes — on exhibit for the first time in the United States — is a compositionally detailed scene of separation and shame. At its center: a voluptuous woman in a forest, whose flaming hair and shirt match the fiery, almost bloody colors behind her, and whose open, white dress melds into the white rocks below her. To her left: A male figure in black, his head turned into his shoulder, covered by his hand. Did she just reject his advances? Tell him he wasn’t good enough? Four years earlier, Munch painted The Artist and His Model, which shows Munch (who would have been in his late 50s) in a bedroom behind a much younger model whose face is burnt-red in color. Munch and the model each look at the viewer in a haze of disquietness. Both paintings suggest relationships that are precarious and dysfunctional — mirroring Munch’s own history.

In 1902, Munch was shot in his left hand while fighting with a former lover, Tulla Larsen, who was distraught over their breakup. Over the next several years, Munch got into numerous public skirmishes with people, some involving weapons. He drank excessively, suffering a nervous breakdown before finally checking himself into a Dutch clinic in 1908. According to Edvard Munch: Behind the Scream, art historian Sue Prideaux’s meticulously researched 2007 biography, Munch was diagnosed with alcohol-induced dementia paralytica. The diagnosis and attending help mark an important milestone in Munch’s life, and Prideaux’s book includes a telling drawing of the clinic’s doctor, Daniel Jacobson, and a woman treating a seated Munch. Munch depicts himself content — smiling, even. The caption reads, “Professor Jacobsen passing electricity through the famous painter Edvard Munch, changing his crazy brain with the positive power of masculinity and the negative power of femininity.”

Munch’s “crazy brain” was integral to his art, and Prideaux, whose godmother was painted by Munch, cites a confessional quote that has become an imprimatur of the artist’s life: “For as long as I can remember, I have suffered from a deep feeling of anxiety which I have tried to express in my art. Without this anxiety and illness I would have been like a ship without a rudder.”

The Scream is not at SFMOMA. Munch made four versions, and the one owned by the Munch Museum, painted around 1910, is too fragile to travel. (Thieves stole another version in 2004. Still another made headlines in 2012 when billionaire financier Leon Black bought it for $119 million — the most money paid for an auctioned painting up to that point.)

But Munch made many paintings that had Scream-like qualities, with similar haunted figures or blood-sky backdrops and compositions. Several are displayed in “Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed” — most notably the 1892 work called Sick Mood at Sunset. Despair. The work has the same perspective as The Scream — two figures in the background, a diagonal walkway, and a bloody sky that crests over a waterway. Instead of a haunted, skeleton-like figure whose hands cup his or her head, a man looks right. His face is featureless, and his downward gaze gives off the impression of someone despondent, in a state of dread and impermanence.

The same year Munch painted his first iteration of The Scream, he painted The Storm, a scene of Norwegian villagers who were huddled against the nighttime ravages of wind and nature’s wrath. The most notable figure, draped in white, has hands cupped against his or her head, à la the figure in The Scream. Almost 50 works — a tiny fraction of Munch’s total output of more than 1,700 paintings — are in the exhibit.

The last time Munch had a major San Francisco exhibit was 1951, when the de Young showed his art, and “Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed” owes its origins to SFMOMA’s recent expansion. The museum contracted with the Norwegian architectural firm Snøhetta, which led SFMOMA’s top staff to go to Oslo, where the Munch Museum is located, kickstarting SFMOMA’s idea to bring the artist’s work to San Francisco. After its run in San Francisco, “Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed” will go to New York’s Met Breuer (the Metropolitan Museum of Art also co-organized the exhibit) and then to the Munch Museum.

“Ruth Berson [SFMOMA’s deputy director of curatorial affairs] and I were in Oslo with our search committee of the board interviewing Snøhetta, and we popped up with the idea of, ‘I don’t think there’s been a Munch painting shown in San Francisco in many, many, many years, and suppose we can conceive of an exhibition here in San Francisco,’ ” Neal Benezra, SFMOMA’s director, said at the exhibit’s preview.

There remains a dearth of public Munch holdings in the United States. SFMOMA has none of his paintings, while New York’s MOMA has just one: The Storm, which it lent for this exhibit. This has contributed to the impression that Munch’s The Scream was his only seminal work, and “has short-changed us as Americans to understand Munch, and the role he played in 20th-century art,” says Gary Garrels, SFMOMA’s senior curator of painting and sculpture.

Pointing out how Munch influenced later artists like Jasper Johns and Tracey Emin, Garrels adds, “Too often, one work becomes that single icon that becomes a stand-in for the artist’s work itself.”

Besides paintings, Munch made 4,500 watercolors and 18,000 prints. (“He’s really one of the masters of works on paper,” Garrels says.) And he had his own lithographic press, which he used until his death at age 80. Munch painted Self-Portrait: Between the Clock and the Bed after the Nazis had invaded and occupied Norway, when he was 76.

Born into strife, his life finished that way. Unlike the bed in other Munch paintings, the bed in this last self-portrait is tidy and made. The clock has no hands. Munch stands next to it. To his far left is a painting of a nude woman. Munch is alone in the room with his art and himself. This is the life that Munch had seemingly envisioned for the end. He’s not screaming. In fact, his mouth is closed, and everything seems perfectly still — as if time had finally stopped for him.

“Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed”

Through Oct. 9 at SFMOMA, 151 Third Street. $19-$25; 415-357-4000 or sfmoma.org.