(Published at KQED on August 2, 2016: https://ww2.kqed.org/arts/2016/08/02/how-to-listen-to-songs-in-a-language-you-dont-understand/)

Many years ago, when I was looking for something to eat and drink on a late night in Hiroshima, Japan, I found the only place that was open. The woman spoke virtually no English. I knew a few phrases in Japanese, including “Eigo Wakari Masuka? (英語分かりますか)” (“Do you understand English?”) and “Watashi wa Amerikahito desu (私 は アメリカ人 です。)” (“I’m an American”). I stayed at the eatery for an hour, “talking” to the woman through gestures, drawings, intonations, and other techniques that academics would call paralanguage. In the end, she gave me a gift — a wooden ornament with my name in Japanese, which she wrote in beautiful calligraphy.

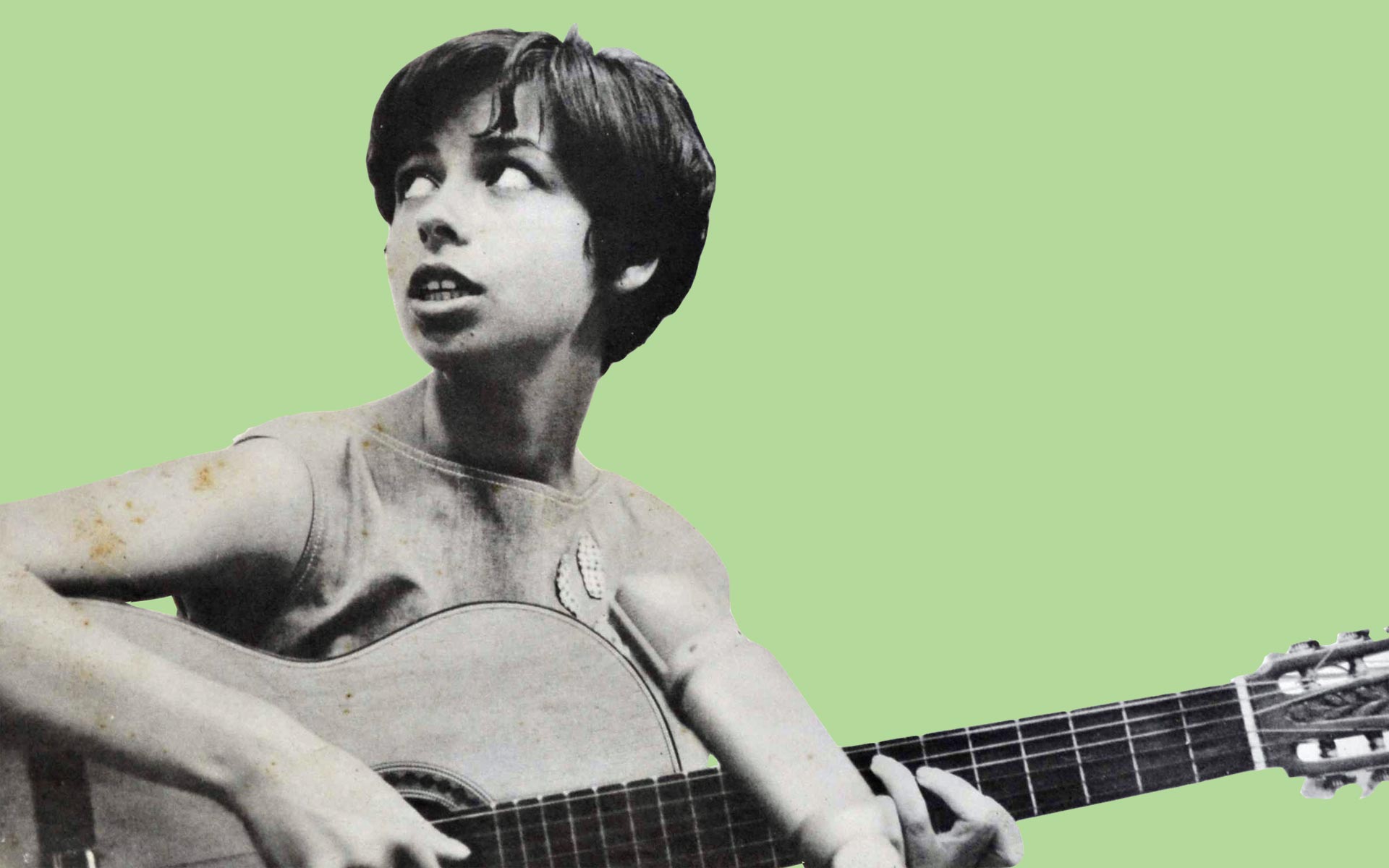

Words are everything. But they can also be completely unnecessary to understanding someone — or a song in a language that’s foreign to your ears. Every day on my computer or my CD player (yes, I still have one), I listen to dozens of Brazilian artists croon on in beautiful Portuguese. I’ve visited Brazil, including the Amazon Rainforest, but the only phrase I still remember to utter is, “Eu não falo Português” (“I don’t speak Portuguese”). I still don’t speak Portuguese, but my lineup of favorite Brazilian songs gets longer every day, and now includes Nara Leao’s “Com Açucar, Com Afeto”, Gilberto Gil’s “Sala do Som”, Vinicius de Moraes’ “Carta ao Tom 74”, Jorge Ben’s “Bebete Vãobora”, Elis Regina’s “Chovendo na Roseira”, and Zeca Pagodinho’s “Maneiras”.

No, I would argue. Absolutely not.What the heck do these songs mean? Am I an absolute dilettante — a pseudo-pretentious but ultimately dumb American — for connecting with lyrics that go over my head (but right to my heart)?

I’m especially convinced of this after speaking with Pat Pattison, a prominent professor at Boston’s Berklee College of Music, where he teaches lyric writing and poetry. Pattison has authored such books as Songwriting Without Boundaries, and his students have included Grammy winners Gillian Welch and John Mayer. In Pattison’s view, a song’s lyrics — the words we hear — are just part of the complete (and very complex) sonic package that’s delivered to our aural doors. A myriad of wordless cues, from a tune’s orchestration to the singer’s inflections, give listeners the insight they need to realize what the song is expressing. Maybe not exactly what the song is expressing, but enough to draw important conclusions, even if those conclusions are challenged upon learning the song’s true lyrics.

Pattison himself often listens to opera sung in French, German, and Italian, all of which he has a basic understanding.

“If I don’t understand the lyrics, I’m then able to appreciate the singing itself — I’m able to listen to the vocal quality and so on,” Pattison says, in a phone interview from Boston. “Even more importantly, I think, I’m listening to a human voice. And in terms of language or communication, a small percentage of our communication takes place with the actual meaning of the words. There’s so much more communication that takes place with tone of voice, with body language.

“We can certainly tell,” Pattison adds, “when a singer is singing a passage whether there’s some innuendo going on, or something that’s sexy going on, or whether there’s anger or whether there’s a helplessness. We hear all of that in the tone quality. So there seems to be a level of communication that’s always present, whether or not we actually have the cognitive meaning of those sounds.”

Remember that happy time, oh I miss…Vinicius de Moraes’ “Carta ao Tom 74” is a good example. Hearing it the first few times, I assumed — because of de Moraes’ almost sentimental intonations, the song’s heavenly backup vocals, and the accompanying minimalistic (and at time dissonant) piano playing — that the song was about something sweet but wistful. I knew that de Moraes was a lyricist of the highest order (he wrote the words for Antônio Carlos Jobim’s “The Girl From Ipanema”), and that Jobim is frequently referred to as “Tom Jobim.” And I knew, from having listened to so many Brazilian songs, that the concept of “saudade” — a longing for a person or a past — is ever-present in the culture. Eventually I translated the song into English with the help of free lyrics sites and translation programs, and I saw that the song’s English title is “Letter to Tom 74,” and that its words include the lines:

Ipanema was just happiness

It was as if love hurt in peace.

You, my friend, there is only one certainty

We must end this sadness

We must invent new love.

De Moraes first released the song in 1974, six years before his death at age 66, as an homage to his collaboration with Jobim, and it’s a clarion call to move ahead and find love anew. Basically, my musical instincts were right.

But they’re not always right. Not at all. The other day, I was listening to Gilberto Gil’s “Sala do Som,” which I guessed had, like “Carta ao Tom 74,” something to do with reflection and moving on. But after doing a lyrics search, I realized it’s about a singer preparing for a show, and trying to rest and also get inspired.

In many ways, enjoying songs with foreign-language lyrics is about first impressions — about liking a song for whatever reason, and then correcting that impression with actual facts. It’s not unlike dating or seeing a person at a party who grabs your interest. You’re smitten. Your brain starts rewarding you with dopamine and serotonin. Language barriers notwithstanding, you’re transfixed.

Do you remember the opera scene in The Shawshank Redemption, when the Tim Robbins’ character, the jailed banker named Andy Dufresne, mischievously plays Mozart’s Canzonetta sull’aria over the prison’s loudspeakers? The song is about planning a seduction to test the fidelity of a royal figure. Not that it even mattered: “I have no idea to this day what those two Italian ladies were singing about,” says Morgan Freeman’s character, Ellis Boyd “Red” Redding, in the film. “Truth is, I don’t want to know. Some things are best left unsaid.”

Which is true. I don’t always want to know the exact lyrics of every foreign-language song that I listen to. I’m content in my ignorance — content to project what I can onto the music, or to just have the music as a happy distraction. Professor Pattison also does that on occasion, telling me: “I purposefully listen to songs with lyrics I don’t understand, simply because I would like to listen without my brain going into overdrive.”

But for me, this “ignorance is bliss” style of listening is really the exception rather than the rule. I ultimately want to know what I’m listening to, in order to test my instincts, and to challenge my intuition. The thing about challenging yourself this way is that your intuition gets better. You learn a few more words in Portuguese (or Arabic, French, Bambara, or another language). You get to know the song better, and you get to know yourself better: what you like in music, and what’s behind your attraction to this work of art that somehow called out to you.

In an episode of my favorite TV comedy series, Britain’s Peep Show, the drug-addled character named Super Hans meets a beautiful Japanese woman who speaks no English. It doesn’t matter. They can’t be separated. “We speak the language of love,” Hans bellows.

With each new foreign-language song I find, I fall a little bit in love, musically speaking. I don’t have to know what the words mean. Not initially. I’m in the early honeymoon phase, and that’s all that matters for now. Without that phase, the other phases won’t arrive.