Peabrain-ism and a Love Supreme

Questions about race? Sure, that seems to be in Drew’s new piece. America’s political issues? That may also be embedded into the reworked flotsam and jetsam that is Drew’s latest international commission. And ideas of beauty? That’s definitely there, as are references to the de Young’s copper architectural bearings. But here’s the thing: In an interview with SF Weekly, Drew said that anyone’s interpretation of his new art is valid. That’s why he gave the work, as he usually does, a formless title (Number 197). Still, Drew strongly hints to SF Weekly that his de Young commission is designed to mimic the notes on a musical score. Not just any score, but a score that’s frenetic and soulful and alive. Something like A Love Supreme by the jazz saxophonist John Coltrane.

“You realize key notes and music and how they’re arranged — you can compose,” Drew says, waving his hands as he scans Number 197. “I compose. I could have given you something very serene. But — boom, I’m going to punch you in the face.”

Not so. Like a scientist in the lab, Drew spends months cultivating objects in his studio — cutting, scraping, plastering, painting, and affixing until he finds the right combinations. He’ll reuse his former sculptures.

In the week before the opening of Number 197, the de Young set up a live camera to let website visitors peer in on Drew’s progress. Drew says he didn’t know about the art voyeurism until three days into the installation. Not that he would have behaved differently. Drew is one of the art world’s most gregarious figures — “I’m a people person!” — with an easy laugh that makes strangers feel completely at ease.

In his mid-50s, he can look back at his life — including his mostly fatherless upbringing in a housing project in Bridgeport, Conn., where he lived across from a landfill; his graduation from the Cooper Union with a BA in fine arts; and a career of important commissions and exhibits, including at the Smithsonian Institution’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden — and say that he’s found an international fan base that appreciates the background and the intensity he brings to his work.

“When I was at the Hirshshorn, there was a security guard there who was running off and telling everyone what my piece meant,” Drew says. “I asked him, ‘Where did you get all that information?’ And he said, ‘From the artist!’ And I kept asking him questions. And he said, ‘You’re the artist, huh?’ I had a friend with me, and he told me, ‘You have to stop him because he’s going all over the place.’ And I said, ‘We’re learning stuff now. Just let him run.’ And I ended up coming out of there saying (about the guard’s ideas), ‘I hadn’t thought of that.’ ”

At the de Young, Drew met with a group of docents who wanted to know everything about Number 197 so they could convey it to visitors. “They wanted to know how I was seeing the work,” Drew says, “and I said, ‘Let’s stop that shit right now. What you want to do is tell me what you’re seeing.’ And it was all over the place — and it was poetic and beautiful.”

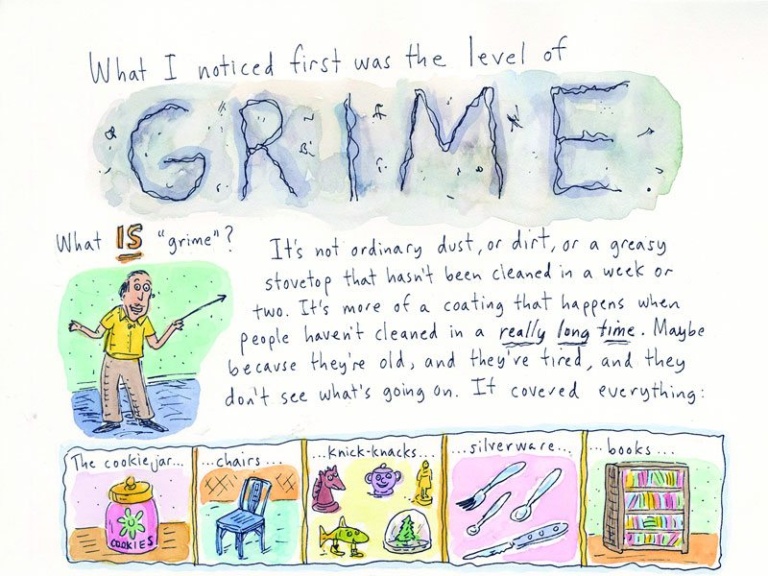

Drew has previously referred to the Bridgeport landfill from his childhood as being akin to “God’s mouth” for its wide spectrum of objects and discarded items. More recently, Drew has spent weeks in the Chinese city of Jingdezhen working with porcelain, a material he had never really focused on. Artisans have been working with porcelain in Jingdezhen for a more than a millennium, and Drew’s first experiments there failed and shattered. He stuck with it, helped by an interpreter who was present from morning to night.

“You can never run from yourself — it’s there,” Drew says. “You start out with this base, and then — boom — it branches off into a number of directions. If an artist is open to digest new things, the possibilities are endless, as big as your imagination. If you have this little pea-brain, you stay in ‘peabrain-ism.’ ”

A week after Drew spoke with SF Weekly, the de Young’s atrium barriers were gone, the exhibit officially opened, and people were milling around Number 197, taking pictures with their cameras. Drew was gone, but his work was making a statement for him — even though he almost quit the project. He says the de Young’s administrators decided they didn’t want him using all three of the atrium’s walls after all. At one point, Drew says he told them they should return Richter’s Strontium to the atrium.

“There was a time,” Drew reveals, “when I had to 86 the show because they had approached me about doing the space, and then said, ‘You’re going to focus on this wall.’ I said, ‘I’m not going to do anything like that. Let’s cancel the show. I quit.’ It’s a perfect three-point perspective. I said, ‘If you’re a museum, act like a museum. These walls are for hanging stuff. You’ll fix them later.’ And they said, ‘Oh, no — there will be holes in the walls.’ I said, ‘That’s what museums do. You’re supposed to get holes in your walls. And then you fix them.’ ”

Drew’s laugh filled the atrium as he spoke, just like his art did — cascading here and there in every direction. It was a beautiful thing to witness, and it was in keeping with Drew’s demanding approach, which he applies to himself.

“Institutions should be challenged,” he says. “And artists should be challenged. Every time.”

“Leonardo Drew: Number 197,” through Oct. 19 at the de Young Museum, 50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive. Free; 415-750-3600 or deyoung.famsf.org.