Cubaist Portrait

Habitually detained by Cuban authorities, Tania Bruguera’s art combines performance with activism. She’s even running for president (although she will not win.)

Published in SF Weekly on June 14, 2017: http://www.sfweekly.com/culture/art/cubaist-portrait/

The Cuban police and officials who have interrogated Tania Bruguera — and who continue to interrogate her whenever she’s on the island — resort to grossly Kafkaesque questioning, which shows how desperate they are to intimidate and discredit the performance artist.

A Cuban native, Bruguera is an internationally acclaimed political artist whose C.V., which stretches back 30 years, includes a Guggenheim fellowship; big exhibits at the Venice Biennale, Tate Modern, and the National Museum Wales; and plaudits from New York’s Museum of Modern Art, which called her “one of the foremost figures in contemporary art” when it bought one of her video works.

But authorities say Bruguera isn’t a real artist. They’ve even said this to her face when, via her own Hannah Arendt International Institute of Artivism, she tried to deliver food, mattresses, and money to an area hit hard by Hurricane Matthew.

“They take over your identity — and decide they can say who you are,” Bruguera tells SF Weekly on a recent afternoon at YBCA, where her new exhibit, “Talking to Power/Hablándole al Poder,” opens Friday, June 16. “They told me [during my detention], ‘You are not an artist.’ We are playing this game where I use art to open spaces of freedom that are otherwise not allowed.

“I was in a position where I was hearing propaganda all the time, and it’s something as an artist that has influenced me,” Bruguera says, adding that she and her father, who died in 2006, had a tense relationship — one not unlike the one that she has with the Cuban government.

“We were not,” she says, “on good terms, let’s say. I think he died believing [in Cuba’s revolution], which was great, though I think he was a little perturbed by how things came at the end.”

Like many Cuban students, Bruguera was forced to attend government rallies as a schoolgirl. And her school forced students to throw eggs at the house of an 11-year-old whose family was leaving Cuba and its revolutionary ways to live abroad. Bruguera refused to toss eggs. Flash forward almost 40 years, and she says that “activism can be when you decide, ‘No, I’m not going to say yes to this.’ ”

If there’s a performance piece that embodies Bruguera’s bravado, it’s Tatlin’s Whisper #6 (Havana version), which she did in 2009 in the patio of Havana’s Wilfredo Lam Center of Contemporary Art. Bruguera set up an elaborate dais where audience members came up and — standing amid a white dove and two soldiers, symbols of Fidel Castro’s 1959 revolution — repudiated what they said were the revolution’s hypocrisies and double-standards. (Amnesty International has also called out Cuba’s restrictions on free expression and its climate of repression.)

“Cuba is a country surrounded by the sea, and it is also an island walled in by censorship,” said one speaker at the Wilfredo Lam Center, where Bruguera invited every attendee to talk uncensored for one minute. “Internet — and, especially, the blogs — have opened some cracks on the wall of information control. … It is time to jump over the control wall.”

Through loudspeakers, each person’s words were projected on the streets outside the venue, turning the event into a public spectacle. At least one speaker praised the revolution. Bruguera, who was teaching and living in Chicago and flew to Havana for the event, had given everyone in attendance cameras to record the proceedings, which were covered by media around the world.

In December 2014, Bruguera tried repeating Tatlin’s Whisper in Havana’s Plaza de la Revolución, where Fidel Castro and other Cuban leaders have traditionally held large rallies. Cuban authorities arrested her on the way to the event, prompting a global appeal campaign that put pressure on the government to release Bruguera along with other artists and activists who were detained in the crackdown.

Bruguera was held on and off for eight months before flying back to New York, where she is now doing an art residency. “Talking to Power/Hablándole al Poder,” is a retrospective of Bruguera’s projects that allows her to update them as she pleases.

“Are art projects that are politically and socially inclined able to survive the moment that gave them the need to exist?” asks Bruguera, wearing a swirling ribbon supporting immigrant respect, which each YBCA attendee will also receive. “Here you will see some pieces that have probably died — probably do not make sense anymore — but we’re trying to update them, to ask, ‘If this piece were to be updated, what would be the issues?’ ”

The exhibit also features something unusual for a major metropolitan museum but which fits into Bruguera’s (and YBCA’s) art ethos: an eight-week-long school, called Escuela de Arte Útil (School of Useful Art), that Bruguera and guest instructors will lead and that anyone can attend. The first assignment asks students to “think about a recurrent injustice that affects you, and propose new ways in which the issue could be addressed.”

Bruguera calls her YBCA exhibition and eight-week school “an experiment.” One of her own recent campaigns is called “#YoTambienExijo,” which translates into “I also demand.” That project began on Dec. 17, 2014, after the United States and Cuba announced the resumption of diplomatic relations and the end of the U.S. embargo. That same day, Bruguera wrote an open letter to President Barack Obama, Cuban president Raúl Castro, and Pope Francis (who helped broker the U.S.-Cuba thaw) to go beyond words.

She implored Raúl Castro to implement “a politically transparent process in which we will all be able to participate, and to have the right to hold different opinions without punishment. … As a Cuban, today I demand there be no more privileges or social inequalities. The Cuban Revolution distributed privileges to those in government or deemed trustworthy (read: loyal) by the government. This has not changed.”

She says that Cuban authorities detain her every time she returns to Cuba, and interrogate her for at least six hours at a time — either when she arrives at the airport, when she leaves, or during her stay. When, during her most recent detention, the state police prevented her delivery of food, mattresses, and money, she demanded they inform her of which law “that says I cannot do this.”

Bruguera says she turned the questioning around because “it was my chance to ask questions of the system. I wanted them to recognize that what they were doing was completely illegal and completely stupid.”

Bruguera says she’ll continue to go back to Cuba because “I always have this belief that the work about Cuba should be done in Cuba. Positioning yourself that way puts an ethical element on the project. It’s easier to stay outside of the danger zone and say whatever you want. … And I feel that political art is art that deals with consequences. It’s not really about criticizing; it’s about understanding how to challenge power, and in the process understanding what are the consequences of that.”

Another example of Bruguera’s artistic daring: In October 2016, she announced her candidacy for Cuba’s presidency, which Raúl Castro will relinquish in 2018. By voicing her intentions, Bruguera encouraged other Cubans to run, too. They have no chance at winning — none at all, as the presidency is expected to be given to Miguel Diaz-Canel, First Vice President of the Council of State of Cuba. Still, the point is not to win, but to spotlight Cuba’s lack of democracy.

“Talking to Power/Hablándole al Poder” shouldn’t just be seen as an anti-Cuban government exhibit. Nor should Bruguera be considered just as anti-Cuban government artist. Bruguera essentially creates art and performs against all governments that inhibit free speech. Her universalism is implicit in her art. In practical terms, Bruguera says that she brings an international perspective with her when she visits Cuba, and a Cuban perspective when she’s in the United States and other countries. Her art is multicultural, appealing to anyone who’s lived under a regime — or even a household — where “the rules” apply differently to different classes. Bruguera holds a Cuban passport but now lives and works in the U.S, and the YBCA exhibit coincides with the presidency of Donald Trump, who’s trying to implement anti-immigration policies and other legislation whose venality seems familiar to Bruguera.

Curated by Lucía Sanromán, YBCA’s director of visual arts, and Susie Kantor, a curatorial associate, “Talking to Power/Hablándole al Poder” is Sanromán’s first bona fide project at Yerba Buena, and one that she originated from start to finish. Hired by YBCA in 2015, she tells SF Weeklythat Bruguera fits in well with the museum’s vision to being “a citizen institution, to become a more democratic platform for cultural change. It became very important to invite an artist who does that naturally. She’s a remarkable, conceptual, interesting, challenging artist.”

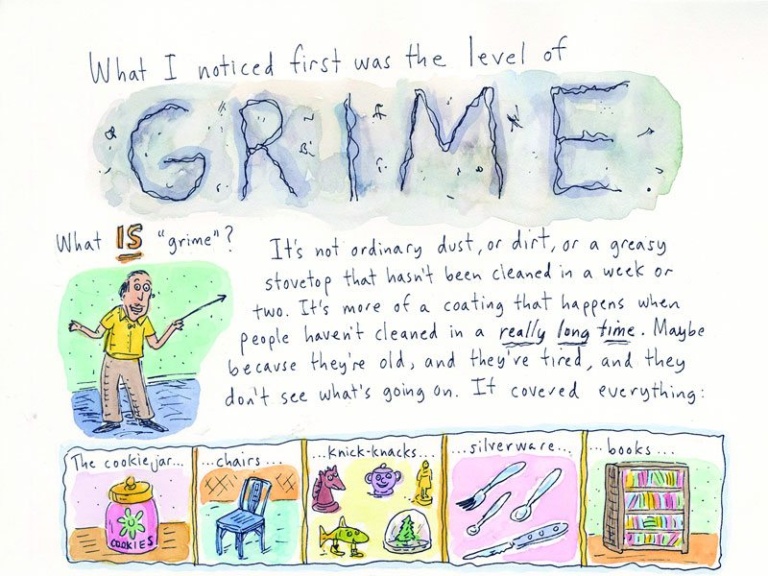

Bruguera blurs the lines between art and activism. Eliminates them, in fact. If she has to go to jail, then fine. If she has to endure truculent comments and interrogation from police, then fine. For her performance called The Burden of Guilt, which references indigenous Cubans who rebelled against Spanish colonizers, Bruguera ate dirt and hung a dead lamb around her neck. In her performance called Self-sabotage, which centers about Bruguera’s lecture about art and politics, she employed a loaded gun that she held to her head. Whatever it takes to get people thinking beyond their preconceptions — beyond the art world into the “real world” — Bruguera will do it.

“Talking to Power/Hablándole al Poder”

June 16 – Oct. 29 at YBCA, 701 Mission St. $9-$10; 415-978-2700 or ybca.org.