VISUAL ART: Roz Chast and the Influence of Anxiety

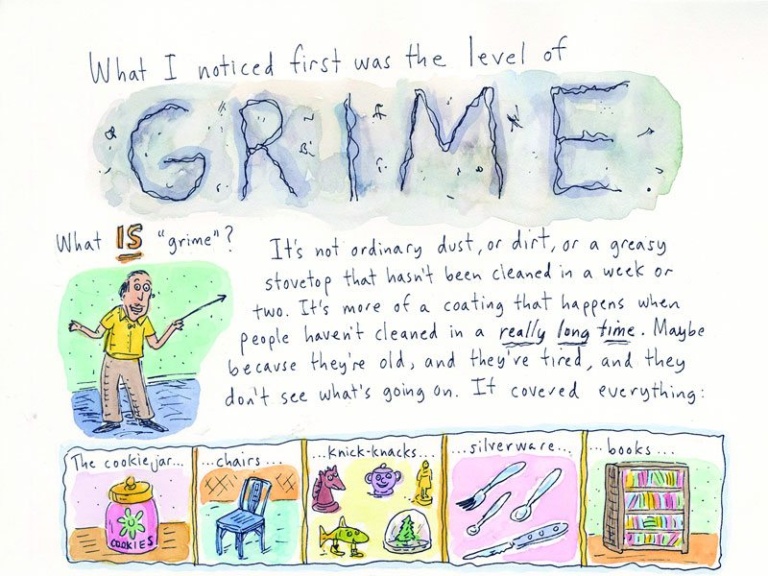

(Published in SF Weekly on May 4, 2017: http://www.sfweekly.com/culture/art/roz-chast-and-the-influence-of-anxiety/) Roz Chast is very funny. Everyone who reads her New Yorker cartoons knows this. In fact, that’s all they really knew about Chast until 2014, when she published her graphic memoir, Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, which details her stressful childhood and the demanding…